The prime functions of engine oil are to lubricate, cool, clean, protect and seal. In the early days of the automobile neat mineral oil was used to perform these functions. Improvements in engine design and engineering techniques soon lead to parts being manufactured to finer tolerances, higher engine operating temperatures, more power and increased speeds.

Consequently, lubrication problems started to occur. Oils deteriorated rapidly, wear rates increased, engines failed and performance was generally unacceptable. In the early 1900s it was discovered that the addition of chemicals, referred to as additives, could improve the performance of the mineral base oils.

Oils deteriorated rapidly, wear rates increased, engines failed and performance was generally unacceptable. In the early 1900s it was discovered that the addition of chemicals, referred to as additives, could improve the performance of the mineral base oils.

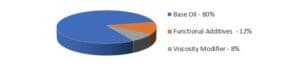

Today engine oils may contain anything between 3% additives in a basic monograde oil and up to 30% in a superior high performance multigrade lubricant. Following is a typical composition of a modern good quality multigrade engine oil:

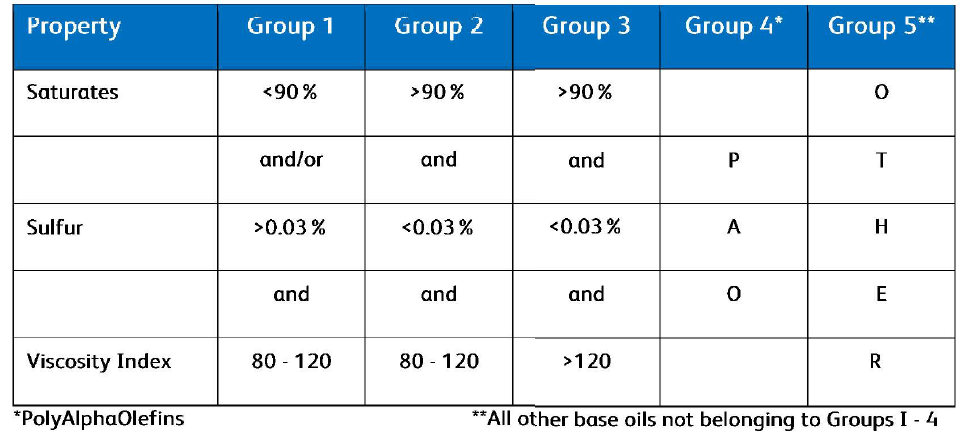

The base oil component of engine oils may be mineral, synthetic or semisynthetic (a mixture of mineral and synthetic stocks). Most lubricants sold today are still blended using mineral base oils. Synthetic base stocks are used whenever petroleum (mineral) based oils have reached their performance limit. Synthetic lubricants have improved high temperature characteristics and are more stable over a wide range of operating temperatures.

Additives are extensively used to improve and maintain modern oil performance. Following is a brief discussion of the additives found in reputable brands of engine oil:

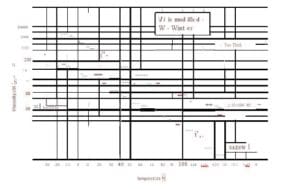

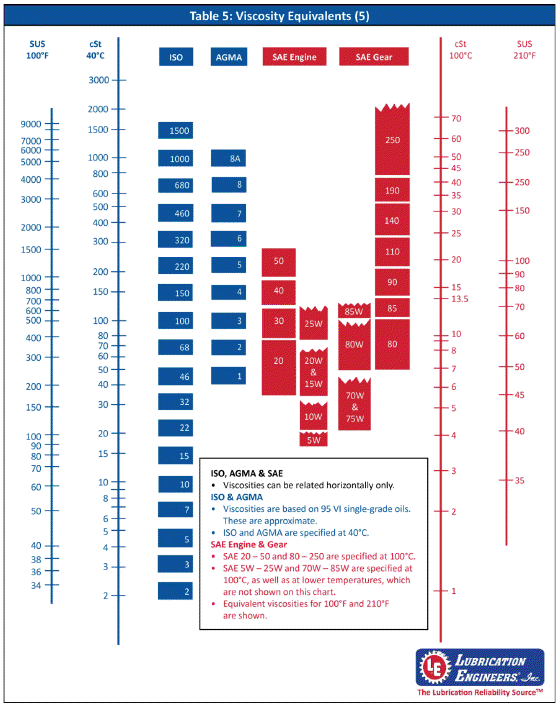

Viscosity Modifiers (also called viscosity index improvers) are used to produce multigrade engine oils. They reduce the tendency of the oil to thicken with decreasing temperature and also resist thinning out at elevated temperatures. Viscosity modifiers (VM’s) are not used in monograde engine oils and if the oil in the above example was a monograde, the 8% VM would simply be replaced by base oil.

Detergents operate on high-temperature surfaces, such as the piston-ring area and the piston under-crown, to prevent the formation of harmful deposits on these surfaces.

Dispersants help to keep internal engine surfaces clean by finely suspending contaminants in the oil until they can be safely removed at the next oil change.

Antiwear Agents protect metal surfaces against wear when the lubricating film breaks down. Zinc dialkyl- dithiophosphate (ZDDP) is a long-used favourite to reduce friction between metal surfaces. Some oils also contain friction modifiers to reduce friction even further but their effectiveness tends to diminish during the life of the oil.

Antioxidants inhibit oxidation of the oil. Oxidation results from exposure of the lubricant to oxygen at high temperatures. The results of such exposure accelerate aging of the oil contributing to oil thickening, sludge and deposits. Antioxidants therefore also help to keep engines running clean.

Rust and Corrosion Inhibitors coat metal surfaces inside the engine to provide a protective film, preventing moisture, oxygen and acids from reaching the metal and causing rust and corrosion.

Pour Point Depressants (PPD’s) provide good oil flow at low temperatures. Oil contains wax particles that can congeal and reduce flow when cooled down. PPD’s modify wax crystal growth at low temperatures and oil continues to flow smoothly.

Foam Inhibitors do not prevent air from mixing with the oil. Foam inhibitors weaken the surface tension of the air bubbles that are formed allowing them to ‘burst’ more readily and thereby reducing foam.

Another critical characteristic of engine oil is its ability to neutralize acids that are formed during combustion of the fuel. The Total Base Number (TBN) measures the ability of engine oil to neutralize these acids. Detergent and dispersant additives (detergents in particular) are highly alkaline by nature and contribute to the neutralization of acids by proving the engine oil with an alkalinity reserve (TBN).

Although additive technology has improved significantly over the years, the ever increasing stress placed on the oil by modern engines demands that the oil still has to be changed at regular intervals as prescribed by engine manufacturers. Reasons for changing the oil are as follows:

- To drain contaminants out of the engine when the used oil is replaced. Contaminants include dirt and dust, unburned fuel, combustion byproducts, water/coolant, wear metals and cross-contamination with other lubricants.

- Additives are consumed during the service life of the oil in the engine and may get depleted.

Then why not simply put more additives into the oil? You can’t necessarily improve the oil’s performance by increasing the additive concentration. In fact, you can make things worse. Engine oils are carefully designed and finely balanced lubrication packages that are scientifically formulated and rigorously tested before they are released in the market. By upsetting this delicate balance you will produce different results than those originally intended. This raises another issue…supplemental oil additives.

On their own the original additives in modern engine oil are extremely effective but they can become harmful if used in combination with aftermarket or over-the-counter oil additives. It is therefore no surprise that engine manufacturers do not approve the use of supplemental oil additives. When using a properly formulated motor oil you do not need any additional additives whatsoever. In fact, the additives you may put in can react negatively with the additives the oil company has carefully blended into the engine oil and may result in engine damage and even engine failure.